University of Oxford

11a Mansfield Rd

OX1 3SZ

UK

Agriculture occupies half of the world’s habitable land and is probably the largest driver of global biodiversity loss. Yet, despite the link between farming and conservation, our current approach for managing the environmental impacts of food is failing.

Today, responsible sourcing relies heavily on certification schemes as a proxy for biodiversity. We trust that if farmers meet these standards, it will increase the abundance and richness of species on the ground. However, research by former ICCS M.Biol student, Vanessa Wynter, suggests this trust may be misplaced. When she analysed coffee systems globally, she found that simply being shade-grown (a major criteria used by coffee certification schemes) did not guarantee biodiversity gain. Unless the coffee system was very close in condition to native forest, the species loss was still substantial. Other research has found that certification schemes are poor proxies for biodiversity outcomes in farming systems worldwide.

The focus on proxies, and the lack of biodiversity outcome data, has led companies to focus on other issues. Greenhouse gas emissions are fungible and easier to measure than biodiversity, and industry has heavily adopted them; today most food companies know their corporate and product carbon footprints and are optimising them. However, intensive monocultures can be very carbon efficient, but have virtually no biodiversity. Systems with the low carbon footprints per kilogram can achieve this by maximising yields through, for example, large amounts of pesticide.

We need to fundamentally change how we quantify food’s environmental impacts. The goal must be to measure biodiversity outcomes, not just practice adoption, and not just greenhouse gas emissions.

With HESTIA, we are building the open-source infrastructure to standardise and distribute data on the environmental outcomes of food production. We have just released HESTIA v1.1, which provides 220 datasets describing 100 crop commodities across 50 countries, based on 135,000 farming cycles globally.

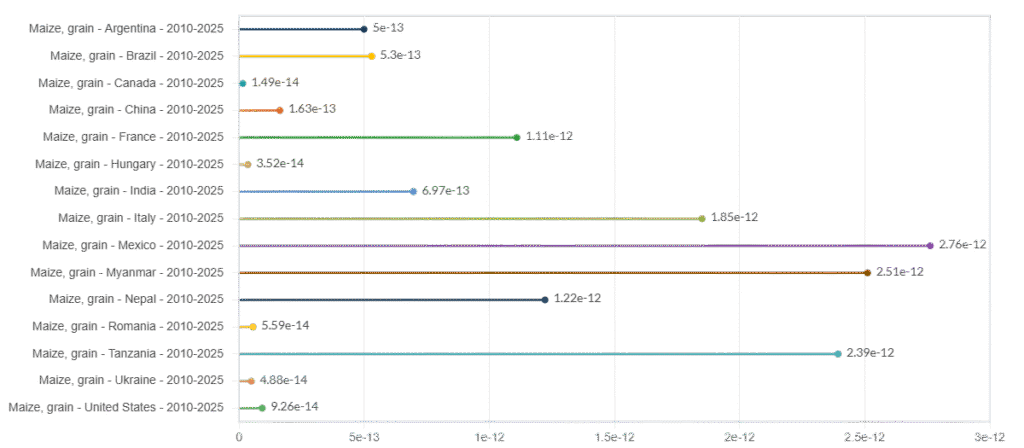

Our work on biodiversity has a long way to go – we need more methodological development and better on-the-ground data. Nevertheless, with our version 1.1 release, we now provide biodiversity outcome data alongside other indicators (such as greenhouse gas emissions and water use).

With HESTIA we are creating shared sustainability data that allows researchers, farmers, businesses, policymakers, and NGOs to see the true cost of production. Our goal is to ensure that everyone has access to the same high-quality evidence.

Maintaining HESTIA as a true digital public good requires the foresight and backing of the organisations supporting research (including governments, NGOs, and philanthropy). If we can continue to secure this foundation, we can continue to align the demand and supply of food with environmental outcomes, and start re-building the food system to leave more space for nature.

Figure 1. The biodiversity loss caused by the use of farmland for maize worldwide. Measured in PDF*year (PDF stands for potentially disappeared fraction, representing the proportion of species richness lost in a given area over time relative to a natural baseline). This metric integrates the intensity of land use, the regional vulnerability of species, and the duration of the agricultural cycle. In general, farming maize in threatened tropical or Mediterranean biomes drives relatively high biodiversity loss compared to other regions.