University of Oxford

11a Mansfield Rd

OX1 3SZ

UK

By Harry Fonseca Williams.

Tsavo East National Park is gigantic. It is the largest national park in Kenya measuring nearly 14,000km2 (roughly the size of Montenegro) and has arguably some of the best game viewing in East Africa. The game is dominated by elephants and is known to have some of the most impressive tuskers (elephants of either sex whose tusks touch the ground) left on the African continent.

A “super-herd” of elephants in Tsavo East ©Harry Fonseca Williams

Back in 2010 an award-winning crew, led by Directors Mark Deeble and Victoria Stone, moved into this ecosystem to make a film about elephants. Eight years later they were to finish the film known worldwide as The Elephant Queen, a 96-minute cinematic masterpiece chronicling the life of Athena, a matriarch, and her elephant herd. The film focuses not only on elephants but on many of the lesser-known species who depend upon elephants for their survival, be it carrying killifish eggs from waterhole to waterhole or digging and maintaining the wallows which critters such as bullfrogs and terrapins rely on. It shows elephants as the “keystone species” or “ecosystem engineers” they are renowned to be.

A female tusker called Medora in Tsavo East, no doubt an old friend of Athena – The Elephant Queen ©Harry Fonseca Williams

The film was acquired by Apple TV+ who launched it internationally to critical aclaim, but now ‘The Elephant Queen’ is going where no film has gone before. As part of The Elephant Queen Outreach, a team of engagement specialists will be touring through some of the human-elephant conflict hotspots of Kenya bringing this epic film on a huge screen with a dramatic speaker system to these marginalised communities on a 40-foot specially designed mobile cinema truck.

The big question is what will this huge endeavour actually achieve? On the one hand it will undoubtedly bring pleasure to all those who have the good fortune of seeing Kenya’s astonishing wildlife as they never have before, and hearing an award-winning score on giant speakers, but can such an exercise go beyond this to actually having a conservation impact?

Measuring the impact of such an event is incredibly nuanced. Watching a film very rarely changes behaviour, but it can initiate shift in attitude, give viewers new information and poise them in readiness to change a behaviour. But what behaviours need changing? What is really achievable through viewing a film? And how can this data be used moving forwards?

Save the Elephants want to know and are measuring the impact of this mobile cinema. After many laborious months planning the study, a framework that hopes to capture the conservation impact has been developed with endless advice from Diogo Verrísimo of the ICCS. The individual quantitative impacts of viewing ‘The Elephant Queen’ are going to be studied using questionnaires on everyone from young adults all the way to 80+ year olds alongside more qualitative interviews conducted with chiefs and sub-chiefs at each venue. The questionnaires are based primarily on the Hazard-Acceptance Model which assumes the ultimate goal to be for communities to tolerate elephants. It is hoped that viewing ‘The Elephant Queen’ may inspire audiences, instilling some empathy for elephants and initiating a micro-shift away from the conflict frequently seen in these edge communities towards one of tolerance and coexistence. At Save the Elephants we appreciate this is a long-term goal and even our follow-up study 3-4 months after the mobile cinema is initially screened in a community may not capture a huge shift in the relationship between humans and elephants, but in comparison to our control groups who will be involved in a snakebite awareness activity done in collaboration with East African Venom Supplies (formerly BioKen) we expect to pick up on any changes that might occur.

There are many ways impact can be measured and we cannot hope to cover them all. The logistical challenges involved in a mobile cinema and impact assessment mean even the collection of this baseline data is providing endless challenges. The mobile cinema is conducting two or three screenings a day and moving location every day. It is also targeting some of the least accessible communities in Kenya.

Moving campsite daily alongside trying to get fed, keep clean and avoid missing any of the screenings will present numerous issues, add in to that trying to persuade a selection of viewers to miss out on this rare opportunity to watch the film on a big screen and instead act as the control group, spending an hour and a half learning about snakes and snakebites.

A side-effect of this study is an opportunity to identify the communities struggling most with elephants, gather indigenous knowledge on how earlier generations coexisted with elephants and begin the preliminary work on planning how ‘Save the Elephants’ can begin to move into some of these communities and provide interventions to reduce conflict with elephants, using beehive fences, smelly elephant repellent, watchtowers and alternative crops amongst a huge array of other tried and tested methodologies.

Very few film based educational outreach programmes of this magnitude have ever been undertaken and even fewer have had their impact assessed. For all involved it has presented an array of challenges to solve, but by the end everyone hopes it will have inspired future generations of elephant conservationists, and we will be in a strong position to move into Kenya’s most elephant conflicted communities to begin the groundwork of creating coexistence with elephants.

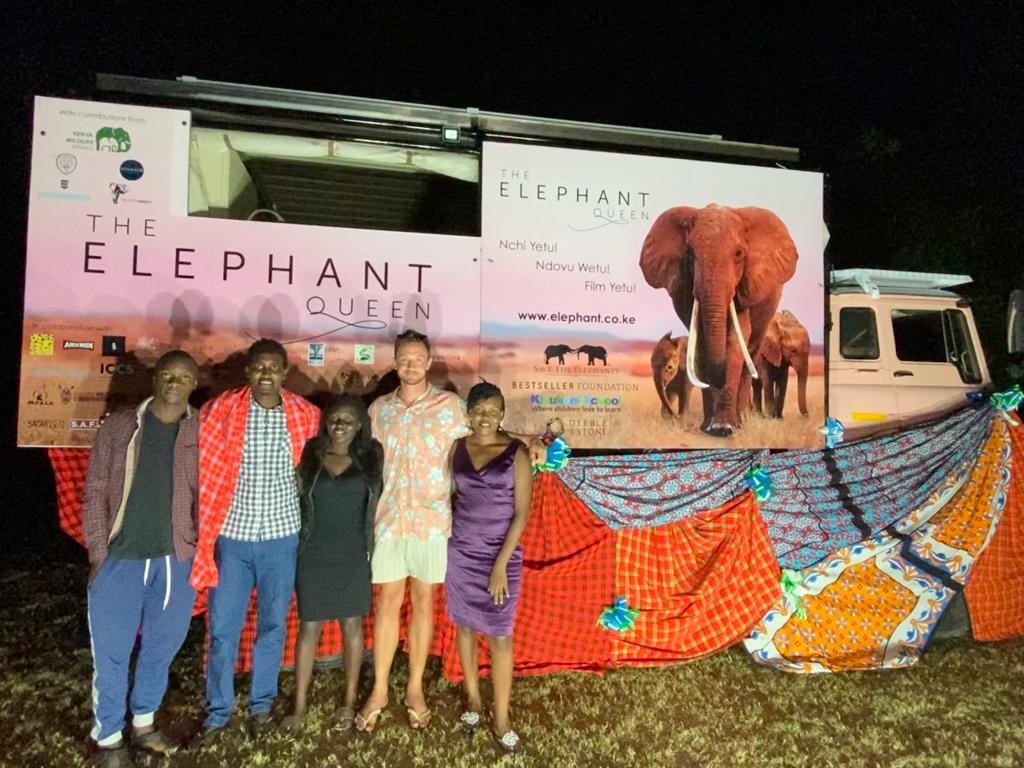

The Impact Assessment Team from Save the Elephants (Left to Right): Brayo Mwalavu, Kennedy Lemaiyian, Gladys Serem, Harry Fonseca Williams and Jocelyn Welah.

A screening of “On Trial”, performed by The Youth Theatre of Kenya was created by The Elephant Queen Outreach with writer Lizzie Jago. The play sees Athena go on trial for killing a young human boy and gets right to the nub of human-elephant conflict. The audience are engaged by playing the role of the jury in debating and deciding the fate of Athena and how the final acts of the show play out. ©Harry Fonseca Williams

The Mobile Cinema during pilot screenings of The Elephant Queen in Kilifi, Kenya. ©The Elephant Queen Outreach