University of Oxford

11a Mansfield Rd

OX1 3SZ

UK

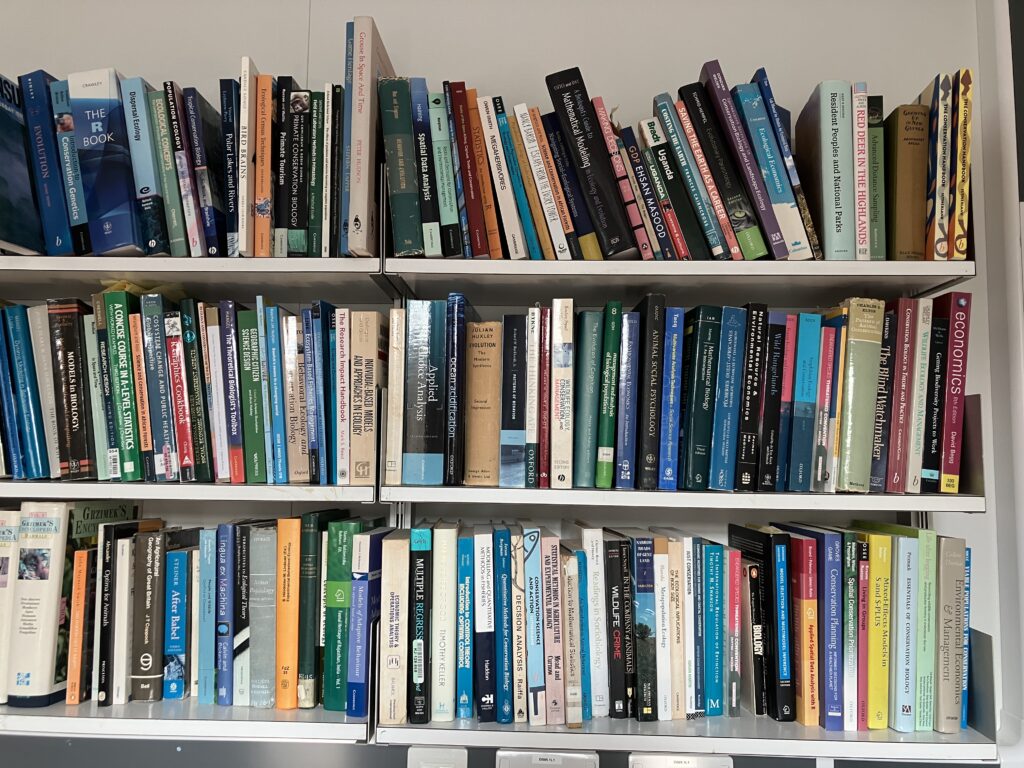

This week I have been moving out of the Biology Department’s temporary accommodation into our brand new Life and Mind Building. A very exciting time but one that involved a bit of introspection because our new offices only have 2 metres of bookshelf space. It’s a rather strange unit of measurement for knowledge, but I have accumulated a library of at least 12 metres over forty years of academic life, which now has to find a new home.

As I searched through it to choose the very few books that would be able to find refuge on my new bookshelves, I found myself back in my PhD days, when I engaged with books with an intensity that I just don’t have time for now. No flicking to find the quote, example, definition that I need to prove a point, but days of poring over equations, pseudocode, chains of logic, trying to think through how what seemed so easy and obvious on the page could translate into the analysis I was trying to do.

The library, as it accumulated, became quite eclectic, reflecting my development as a researcher. Lots of primers in economics from my PhD, texts on natural resource management and statistical modelling, a lot of ecology, and some very niche books on particular geographies and species I was working on at particular times in my life. Some books that date from my time as a newly appointed lecturer were more like self-help books; how to get a PhD, how to supervise and teach. Some surprising books that people who had passed through my lab had left behind, and some gifts, including books written by friends and colleagues with dedications in them.

I thought these books of mine deserved a tribute, so here is a quick run-through of a very few of them, which take me straight back to a place and time:

From school – Richard Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene, which I read just after I had got my place at New College Oxford, after he’d interviewed me. At interview, I wondered why everyone else had been so overawed; I realised once I’d read it! David Attenborough’s Life on Earth, which my mum bought me, written so inspiringly that I still am excited by stromatolites. And my trusty and now hopelessly outdated Oxford Dictionaries of Science and Biology which fuelled my A level revision.

From undergraduate – my trusty copy of Begon, Harper and Townsend’s “Ecology”, beautifully comprehensive, with examples I was still using when I started teaching undergraduates. As well as the Blind Watchmaker which I bought with a book prize in tribute to my tutor. And dating from just as I started my PhD, E.O. Wilson’s “Biodiversity”, defining a new term which now seems so commonplace it must have been in the discourse for ever.

During my PhD I started getting serious with economics. I added Begg, Dornbusch and Fischer to my textbook collection, to get my head around first-year microeconomics. I enjoyed Raiffa’s book from 1968, set by my class tutor at the London School of Economics, on “Decision analysis: Introductory Lectures on Choice under Uncertainty”. Like many of my older books, it reminds me that the core problems that we are addressing now are not new, and nor, in many cases, are the ways we need to think about them. The book I read and re-read during my PhD, was Colin Clark’s “Mathematical Bioeconomics: The Optimal Management of Renewable Resources”, published in 1990. What a role model of clarity, concision and logic, which prompted endless inadequate scribbling of equations on bits of paper.

Some books changed the way I thought about science. I absolutely loved Hilborn and Mangel’s “The Ecological Detective: Confronting models with data”. It challenged the orthodoxy and flipped the way I thought about modelling and experimental design. Peters’ book on the ecology of body size, and Owen-Smith’s book on megaherbivores fascinated me, given that I was working on elephants and thinking about how life histories were shaped by context.

Other books were of the “oh let’s just take a look at what X and Y say about how to do this” type. They gave me foundational understanding of statistics, population modelling, social research methods, conservation, that I could then pass on to my own students in due course: Getz and Haight; Mangel and Clark, Houston and Macnamara; Brown and Rothery; Mead and Curnow; Pearce and Turner; Caughley and Sinclair… all these names are rhymes that go around and around in my head; reassuring, insightful (if, sadly, also all male).

As new disciplines took shape, books that spanned these new areas started to come out. Along with the early classic by Pearce and Turner, I can’t not mention the outstanding Edwards-Jones et al “Ecological Economics: an introduction”, published in 2000 before Gareth’s untimely death; much missed. I also enjoyed Colin Price’s “Time, discounting and value”, which took a slightly radical view of how to think about how value changes over time. Davies and Brown’s edited volume “Bushmeat and Livelihoods: Wildlife management and poverty reduction” brought these two areas together and sparked a whole interdisciplinary line of enquiry. As I started to write books myself, I was inspired by Bill Sutherland’s series of textbooks, which were a lesson in how to write clearly and interestingly for people coming into a subject and needing a guiding hand.

Some of my most useful books are those written about particular species. Based on decades of fieldwork and scientific thinking, they laid the foundations that young researchers like me needed. Clutton-Brock and Albon’s “Red Deer in the Highlands”, for example, and Peter Hudson’s classic “Grouse in Space and Time”. And in Russian and dating back to 1959, given to me in Moscow and never to leave my bookshelf, Bannikov’s “Biologiya Saigaka”, then Fadeev and Sludsky, and later, Sokolov – critical and irreplaceable sources of data and ecological insight.

My saiga books are coming with me wherever I go, and some of the other books that mean the most to me will come too. But I have decided that the rest should be read by others, not put on my shelves at home. When I told my students that I was giving my library away, two of them were in the room picking books excitedly off the shelves within 5 minutes of my message. It was an emotional moment to think that perhaps some of the books that had inspired and guided me, sometimes bent my brain until it hurt, could do the same for someone new. I’m fascinated by the book choices people are making as they browse. I’m not sure that every book will find its soulmate, but perhaps some of them will do for a new generation what these books did for me.