University of Oxford

11a Mansfield Rd

OX1 3SZ

UK

This page contains work published outside of academic journals, including policy briefs, guidance documents and other resources.

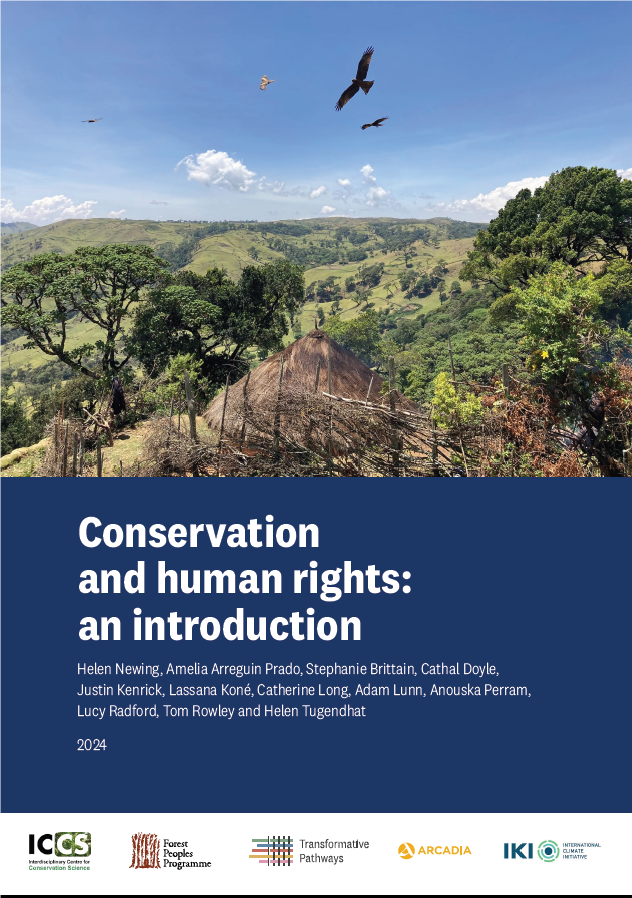

Conservation and human rights: an introduction.

Conservation and human rights have had an uneasy relationship ever since the emergence of the modern ‘western’ concept of conservation in the late nineteenth century. The core strategy of conservation globally has been the creation of uninhabited areas that are protected against any form of human exploitation (an approach known as ‘fortress conservation’). Fortress conservation has often involved forced, violent evictions of whole communities, and has had devastating impacts on the lives, cultures and wellbeing of indigenous peoples and local communities, often in violation of their rights. Since the 1970s, conservationists have made repeated commitments to respect rights, but despite this, forced exclusion continues to be commonplace and violent evictions still occur regularly. Not only is this morally wrong and in violation of human rights, but it is also counterproductive. We now know that many traditional systems of environmental stewardship are sustainable, and that good conservation outcomes are correlated with greater local autonomy and control (Dawson et al, 2024).

However, at the UN CBD COP15 in 2022, nearly 200 countries made a renewed and strengthened commitment to follow a human rights-based approach in conservation. The commitment was made as part of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, which sets out 23 targets and four overarching goals for what needs to be done over the next 30 years to address the global biodiversity crisis. The strong language on rights-based conservation in the Framework provides an opportunity to transform the way that conservation is done and build on common interests between conservationists and the many indigenous peoples and local communities who are struggling to defend their lands, resources and cultures from destruction. To do this, there needs to be a move away from top-down approaches and externally generated priorities, towards greater support for those who live in biodiverse, vulnerable places to conserve their own nature, based on full respect for their rights (Milner-Gulland, 2024).

Several changes will need to take place for this shift to happen, including institutional, political and normative changes in the conservation sector. However, one underlying requirement is a much better understanding amongst conservationists of international human rights law, how it applies to conservation, and what a human rights-based approach means in practice. To help meet this requirement, our new publication introduces the major international human rights instruments and frameworks, summarises how they are overseen and implemented, and discusses how they apply to conservation. It then sets out the most relevant human rights of three groups of people who are particularly affected by conservation: indigenous peoples and local communities, women, and environmental human rights defenders.

Lastly, the guidance presents several practical tools and approaches to help conservationists apply a human rights-based approach. Tools for respecting and protecting rights include social safeguard and due diligence procedures, human rights impact assessments, free, prior and informed consent processes, grievance mechanisms, and processes for remedy and redress. However, following a rights-based approach means more than this. It also means actively supporting rights-holders to assert and exercise their rights and working to ensure that governments and others meet their human rights obligations.

Rights-based approaches cannot be reduced to a set of steps or methodologies alone; instead, they involve a shift away from approaches in which individuals, communities and peoples are treated as the passive objects of external interventions to one in which they are recognised as “key actors in their own development” (UNDG, 2003). The details of how this is done in practice vary from case to case, but in all cases, it involves building on common interests and negotiating where there are differences in interests, with full respect for individual and collective rights as an underlying bottom line. Our guidance presents three tools that have proven useful in identifying and building on common interests: the Whakatane Mechanism, which is a conflict resolution methodology adopted by the IUCN, participatory mapping, and participatory biodiversity monitoring. The guidance ends by exploring what a rights-based approach means for two common types of conservation project that often affect Indigenous peoples and local communities. These are livelihoods projects and projects related to human wildlife conflict.

The need for conservation to be rights-based is now firmly embedded at the heart of international policy. Now it needs to become embedded in practice throughout the conservation sector. For this to happen, human rights will need to become a standard part of formal conservation training programmes. More immediately, each of us who works in conservation needs to take responsibility to ensure that our own work follows a rights-based approach.

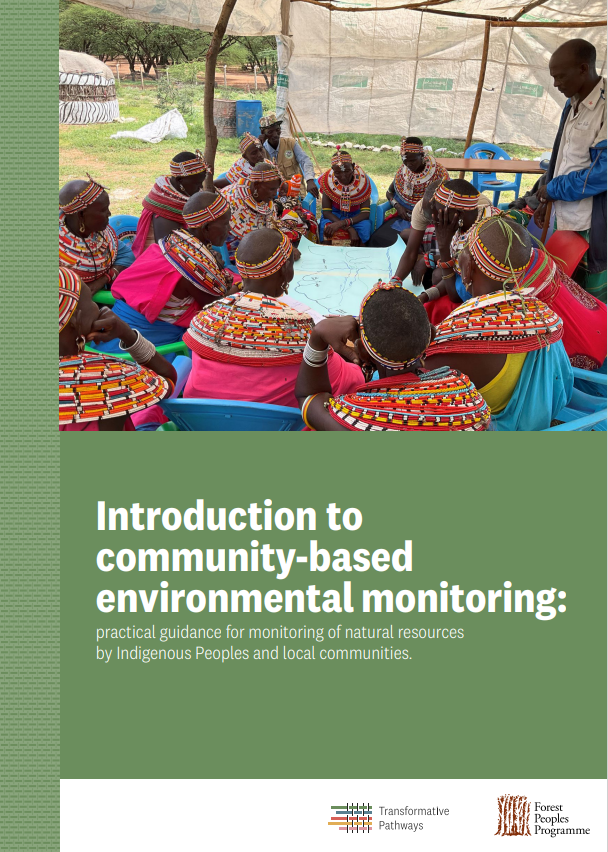

A new resource for Community-Based Biodiversity Monitoring

In the face of escalating biodiversity loss and the urgent need for sustainable conservation practices, the role of Indigenous Peoples and local communities (IPs & LCs) has never been more critical. To ensure that their actions are recognised and supported in national and international policy, a new guide offers a resource to support IPs and LCs in using new and innovative biodiversity monitoring techniques.

Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities have been monitoring the biodiversity on their lands since time immemorial. They have an in-depth understanding of the unique flora and fauna on their territories, as well as the threats that are facing them. However, this knowledge is often held as stories, observations, songs or chants, and is often overlooked in the development of biodiversity policy.

Recognizing this, “Introduction to Community-Based Environmental Monitoring,” offers a new resource for IPs and LCs and those working with them to support new forms of biodiversity monitoring. Produced as part of the Transformative Pathways project, the guide serves as a tool for communities to assert their land rights and participate more actively in conservation dialogues. By generating and managing their own environmental data, communities can strengthen their positions in negotiations with governments and international bodies.

Maximising ranger-collected data to tackle elephant poaching.

ICCS postdoc Tim Kuiper and Professor E.J. Milner-Gulland partnered with the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority to help tackle elephant poaching through leveraging poaching data collected by wildlife rangers. Ranger detections of elephant carcasses have immense value for tackling poaching – helping park managers track changes in poaching, and strategically direct and measure the performance of different antipoaching strategies. In late 2020, Tim was awarded a Fellowship from the Oxford Policy Engagement Network to translate his PhD research into action in Zimbabwe. Tim’s PhD assessed the reliability of ranger-collected data and how these data were used by park managers in the Zambezi Valley. Learn more about this research here .

The policy brief co-developed with the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority was endorsed by high level management within the organisation, and in late 2022 local partners in Zimbabwe began workshops with ZPWMA staff to start the process of implementing the policy guidelines.

Ensuring the sustainability of customary use on Indigenous and community-held lands

This guide is for local organisations (e.g. community-based organisations and trusted

local non-governmental organisations) which are supporting Indigenous Peoples and

local communities (IP & LCs) in their desire to assess the sustainability of natural

resources on their lands (both terrestrial and marine), and implement activities to

ensure that this use is sustainable, where necessary. It can also be used by Indigenous

Peoples and by local community groups directly. In this guidance, we’re looking at

sustainability simply as making sure natural resources are used in a way that doesn’t

decrease their amount, ensures nature can keep working properly, and aligns with

community understandings about responsibilities to future generations.

The guidance is also available in Swahili, French, Spanish and Thai. Links can be found on this project page.