University of Oxford

11a Mansfield Rd

OX1 3SZ

UK

By Hollie Booth

Background

Populations of marine megafauna – such as sharks, turtles, and cetaceans – have experienced dramatic declines in the past 50 years. These declines are primarily attributed to overfishing, with huge increases in relative fishing pressure. Many large, slow-growing marine species are now threatened with extinction, and this not only jeopardizes biodiversity itself, but degrades the benefits that people obtain from the ocean.

There is an urgent need to halt and reverse these declines. Already, technologies and practices that reduce the impacts of fisheries on marine megafauna are relatively well documented (e.g., BMIS), yet they remain under-deployed in most of the world’s fisheries. Research from my DPhil highlighted that this is in a large part due to social and economic barriers to adoption. These barriers are especially challenging in small-scale mixed-species fisheries, which are ubiquitous throughout coastal waters, and where people are highly dependent on marine resources, including endangered marine megafauna, for their food and income. This can result in direct trade-offs between marine biodiversity conservation and coastal livelihoods.

So, the big question – particularly in the context of delivering global policy goals such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals, the CBD post-2020 framework – is how to manage these trade-offs? How can we reduce catches of endangered marine megafauna, while protecting the livelihoods and well-being of some of the world’s most vulnerable coastal communities?

This was the overarching question that I aimed to answer during my three-year DPhil, with a particular focus on sharks and rays in Indonesia. There is no easy answer because specific solutions need to be tailored to local contexts. However, through participatory action research with fishers and local managers, we did identify some promising and practical solutions. In particular, incentive-based approaches – such as rewarding or compensating small-scale fishers for positive conservation actions or outcomes – could help to alleviate trade-offs between biodiversity conservation and coastal livelihoods

The next step was to work with stakeholders to test, implement and scale these findings. Moreover, as part of my research permit application and reporting process I was formally requested to prepare a policy briefing on the results of my research. As such, an Oxford Policy Engagement Network (OPEN) fellowship was the perfect opportunity to kick off this process, and respond to a request from the Indonesian government.

The project and partners

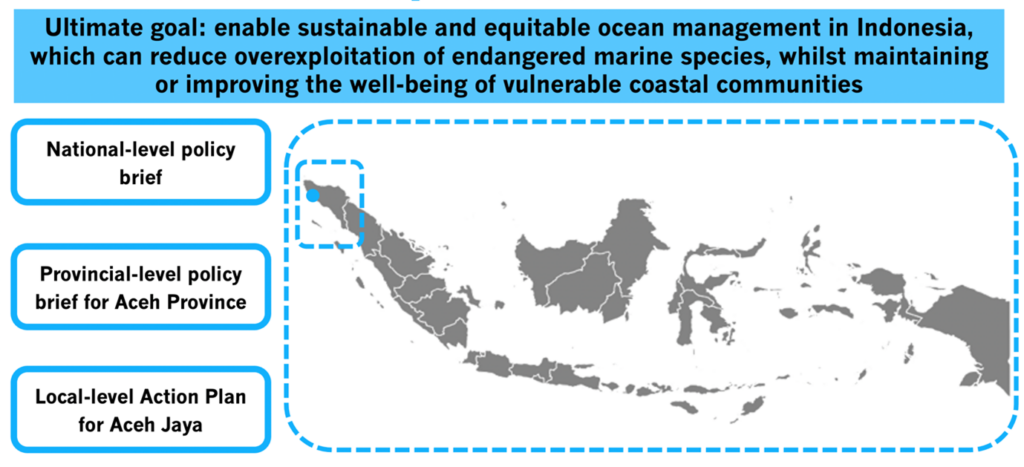

Within this context, the OPEN fellowship aimed to enable sustainable and equitable ocean management in Indonesia, which can reduce overexploitation of endangered marine species, whilst maintaining or improving the well-being of vulnerable coastal communities. We took a multi-level approach to contribute towards this aim, seeking to translate research into national-, provincial- and local-level policies and action plans. At the provincial- and local-levels my fellowship focused on Aceh Province and Aceh Jaya Regency, respectively. This was because part of my DPhil research had focused specifically on a small-scale coastal gill net fishery in Aceh Jaya called Lhok Rigaih, where Critically Endangered hammerhead sharks and wedgefish are frequently captured as valuable secondary catch.

Based on this, key decision-making partners were the Indonesian Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (offices at both national and local levels) and the Panglima Laot (a unique customary fisheries management institution in Aceh Province). These partners were chosen based on pre-existing relationships, as both participants in and end users of my DPhil research. Other key institutions included my Indonesian research counterparts at Institute Pertanian Bogor (IPB) and the UK Centre for environment fisheries and aquaculture science (CEFAS) who I’d be working with as part of a pre-existing UK government funded North-South exchange project regarding marine wildlife trade, and so we were able to synergise. Not forgetting the fishers of Lhok Rigaih themselves, as those who would be most impacted by any new policies.

The results

Following a series of meetings and consultations at national and local levels, we developed a national-level policy brief on integrating incentive-based approaches into national-level conservation and fisheries management policies and a provincial-level policy brief on integrating socio-economic issues into the shark and ray action plan for Aceh Province. We also produced a range of other infographics (in English and Indonesian) and guidance documents on live post-capture release for gill net and longline fishers.

Partners at MMAF gave positive feedback on the strategic importance of the briefings, and we have further follow-up meetings planned on next steps.

“Such an important paper. The Minister is interested in adopting a payment approach to communities to conserve the ocean. However, many things still need to be organised to see how in practice that approach can be implemented… in technical, legal, and financial system. [This briefing] is one of good reference for that.”

Firdaus Agung, Directorate General for Marine Spatial Management, Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries

We have also been approached by the UN Food and Agriculture organisation for translating findings and recommendations into some general international guidance for fisheries managers, which could have global policy impacts.

However, probably the most exciting outcome is that we were able to leverage the OPEN funding alongside a grant from Save Our Seas foundation to establish a randomized controlled trial of incentive-based approaches to bycatch mitigation in Lhok Rigaih, and we’re already seeing positive results.

We’ve named the project ‘Kebersamaan Untuk Lautan’ (togetherness for the ocean). Under the trial we have distributed cameras to and signed voluntary agreements with small-scale fishers. The agreements state we will provide them with direct cash compensation on receipt of video proof that they have safely released any Critically Endangered wedgefish or hammerhead sharks from their nets, and we are already seeing positive results.

Next Steps

Once the trial is complete it will provide empirical evidence on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an incentive-based approach in Aceh Jaya, with recommendations for design and implementation. We are also disseminating key outputs, and have developed a simple website to summarise general findings and recommendations, and act as a repository for the policy briefs, infographics and guidance documents.

In the longer term we hope that recommendations can be formally instituted into policies and plans, with long-term revenue generating mechanisms for example via tourism levies or bycatch levies in commercial fisheries. If successful these mechanisms could deliver positive outcomes for shark conservation and coastal communities, and support the delivery of global policy frameworks such as the CBD, SDGs and a sustainable and equitable blue economy.