University of Oxford

11a Mansfield Rd

OX1 3SZ

UK

Most business models of the 21st century have a net negative impact on nature. They fundamentally rely on using natural resources – oil for fuel, land for infrastructure, cotton for textiles – with few incentives to replace or regenerate what is lost. As of 2020, human-made materials outweigh all living things on earth, and the destruction of nature is testing the biophysical limits of the earth system, on which we all depend. This exacerbates extreme weather events, and even deadly pandemics like COVID-19. The pandemic should serve as a wake-up call to fundamentally reset our relationship with nature, and “build back better” with a “green recovery” to create a more sustainable and equitable future. But how?

The tourism sector has an interesting relationship with nature conservation and sustainability. On the one hand, huge hotels and mass tourism can degrade natural resources and destabilise ecosystems (e.g. the case of Boracay Island in The Philippines). International air travel is also a huge contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. On the other hand, responsible nature-based tourism can generate incentives for conservation, and international travel provides an opportunity for people to connect with different cultures and have meaningful nature experiences.

However, many nature-based tourism companies fail to align their economic profits with social and environmental outcomes. For example, sharks and manta rays are arguably worth more alive than they are dead, due to the income generated from a multi-million-dollar dive tourism industry. However, fishers who depend on sharks and rays for their livelihoods often do not receive the financial benefits of the tourism industry, creating a mismatch of incentives. Neglecting these issues can lead to long-term degradation of the natural assets on which nature-based tourism fundamentally depends. The world needs more business models which can align profit, planet and people. Misool Resort in Indonesia provides a great example, and some important lessons for responsible eco-tourism in a post-COVID world.

The Misool Experience

Having worked in marine conservation in Indonesia during the past 5-years, I’d heard a lot about Misool Resort. They’ve won several prestigious sustainable tourism awards, and researchers have published studies on impressive increases in fish biomass and reef shark populations since their marine reserve was established. This November I was lucky enough to see it for myself.

The resort consists of a small collection of water bungalows on Batbitim Island in Raja Ampat, Indonesia. The bungalows are made entirely from locally-reclaimed wood, and are perched on stilts with steps down in to the turquoise Seram Sea. However, the resort itself is only the ‘tip of the iceberg’ in terms of what Misool has to offer. It’s nestled within a 1,220 km2 marine reserve, which is leased directly from local families, to establish two no take zones (NTZs), where no fishing activity is permitted, and a linking restricted-gear blue water corridor. Hundreds of small islands, fringed by coral reefs, are dotted throughout the Misool NTZ, and serve as habitat for a stunning density and diversity of wildlife.

Shark lark and manta banter

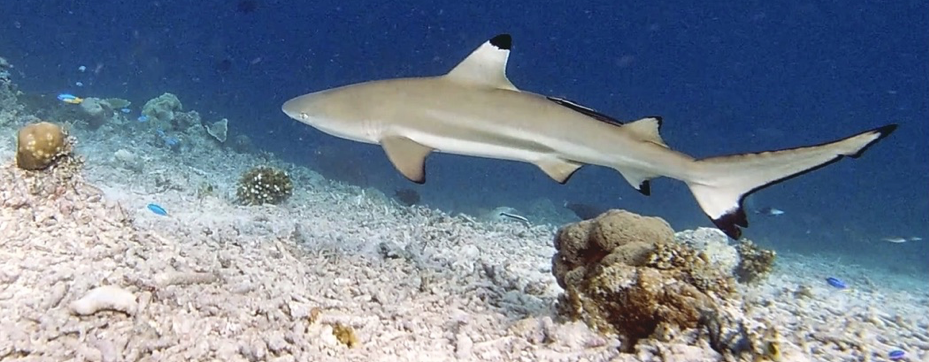

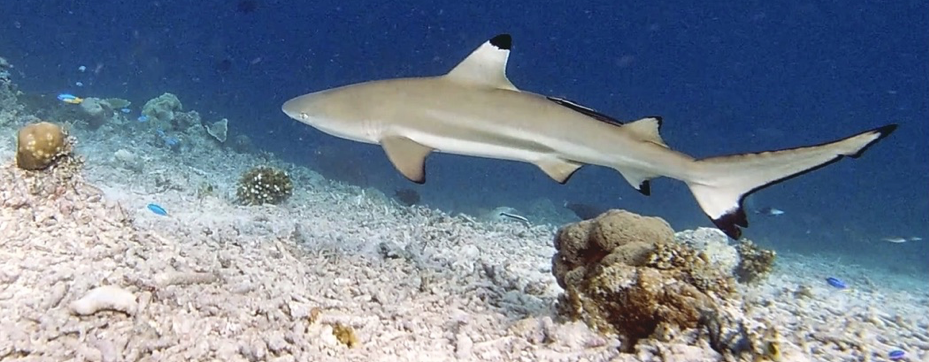

Misool is one of the few places in earth where it’s possible to see reef manta rays and oceanic manta rays on the same dive site. If turtles and sharks are more your thing, then you don’t even need to leave the comfort of your bungalow: green turtles, leatherback turtles and juvenile blacktip reef sharks swim by every day in the resort’s shallow lagoon. If weird and wonderful is more your thing, then Misool has plenty of rare and endemic species as well. I met my first ever wobbegong shark and walking sharks, plus there’s a whole host of macro, including decorator crabs, pygmy seahorses and colourful nudis. On land, you can also meet Papuan Hornbills, sulphur-crested cockatoos and great billed parrots.

Triple-bottom-line, transformational change

However, Misool hasn’t always been like this. When the owners, Andy and Marit Miners, first came across Batbitim island in 2005 it was home to a shark-finning camp. With support from their idealist co-founders/shareholders they established Misool with marine conservation as their primary mission, and it really shows. Misool resort is a shining example of what can be achieved by the private sector in general, and the tourism sector in particular, when success is really measured in triple-bottom-line outcomes. By putting the needs of the marine environment and local people first, the Misool team have transformed a desolate shark-finning camp in to a high-value natural asset, for the benefit of present and future generations.

Spill-over effects

The thriving marine life within the NTZ also improves fish catches in bordering fishing grounds, the Bank Sampah scheme helps to remove marine plastics while creating income for local people. Misool and Misool Foundation employ more than 250 staff, 96% of whom are Indonesian. They estimate that these salaries support around 1,000 people from the local community. Wherever possible, they employ from the local vicinity and promote through the ranks. The current head instructor at the dive centre, Kiki, was first hired as a labourer in 2005 and couldn’t speak a word of English, as was Ali, the head of the kitchen. Today, both of them speak fluent English, are trained to the highest international standards in scuba diving and hospitality management, and act as role models for young ambitious Papuans.

Perhaps even more inspiring is that as well as supporting a thriving socio-ecological system in Raja Ampat, Misool Resort invest a significant proportion of their profits in to conservation work elsewhere. For example, in 2019 Misool Resort donated $358,950 to Misool Foundation, making it the foundation’s biggest funder. These funds are used to support the local government in East Flores to protect manta rays from illegal hunting, via marine patrolling and livelihood-based interventions, with impressive results.

What now for eco-tourism?

Unfortunately, the global tourism industry has been hit badly by COVID-19; in some cases, with knock-on effects on the wildlife populations it helps to sustain (e.g. reductions in wildlife safaris in Africa linked to increases in poaching). As vaccines are rolled out and travel restrictions are reduced, national parks and eco-tourism businesses will no doubt be eager to make up for lost time and income. However, we must not lose sight of a green recovery. We need more companies to take a leaf from Misool’s book, to help society ‘build back better’ after COVID-19. As Misool have shown, when eco-tourism companies make long-term investments in nature and people, the dividends will repay many times over. Moreover, with insurmountable evidence that degradation of nature increases the risk of pandemics, protecting and restoring nature must be placed at the forefront of business plans and stimulus packages.

One option would be for the tourism sector to commit to nature-positive outcomes, such as no net loss or net gain of biodiversity. Many companies in other sectors have already made such commitments, for both carbon emissions (e.g. Microsoft) and biodiversity loss (e.g. Kering); and these aspirational targets, which can be implemented via a hierarchy of actions, could help the nature-based tourism sector to contribute towards protecting and restoring natural assets. For example, by using an ‘offsetting’ type approach, tourism businesses could invest a portion of their profits in to renewing nature, as Misool invests in their reserve and in Misool Foundation. In the marine tourism industry, this could involve payments for ecosystem service schemes to establish no take zones (like Misool Reserve or Shark Reef Marine Reserve in Fiji), or incentives for coastal communities to reduce catches of threatened sharks and rays (as per my on-going research project in Lombok, which you can also participate in if you have visited Lombok yourself).

Looking ahead, protecting and restoring nature while meeting human needs will require a bold vision in a post-COVID economy. Since many tourism companies fundamentally depend on nature in order to have profitable businesses, perhaps it’s time for the tourism sector to take a leaf from Misool’s book and adopt nature-positive targets as part of a green recovery?

Hollie is a PhD researcher in the ICCS research group at the University of Oxford. Her research focuses on understanding and managing socio-economic trade-offs within shark conservation. You can contact her/read more about her research here:

- Email: hollie.booth@zoo.ox.ac.uk

- Twitter: @hollieboothie

- Instagram: @the_hollitype

- ICCS research profile: https://www.iccs.org.uk/person/hollie-booth

- Google Scholar profile: https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=V-vwRPoAAAAJ&hl=en